About 250 wars have broken out since the end of the Second World War in 1945. These wars are estimated to have killed around 90 million people (86 million according to the Coalition for the International Criminal Court).

That puts them on an approximate equal level with, if not ahead of, the death toll of the two world wars taken together.

How could that happen, and why have most of us barely noticed what was going on?

To address the second question first, the post-1945 wars are fundamentally different in nature from the two world wars. There was not a single war between the developed countries of the northern hemisphere; nearly all of these wars took place between or within the poor countries of the South(3). Only very exceptionally did one of the northern countries suffer significantly in one of these wars, as France did in Algeria, the United States in Vietnam and the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. Each of these three wars left a deep and long-lasting impression in the collective memory of one of the members of the northern club, mainly because a significant number of their citizens died as soldiers. The fact that many more died on the other side was much less noticed. A fortiori, a war that is victimless for the North receives little notice beyond occasional gruesome television footage. People can die in wars by the million in the South without the North taking notice, except in cases of blatant genocide, such as Rwanda and Cambodia, and then only ex post facto, when the deed is done.

If we want to understand why all these conflicts took place since 1945, we need to give some thought to the nature of military conflict. Violent conflicts erupt for a multitude of reasons: religious belief; ideology; Klassenkampf (i.e. economic conflict in the sense of Marx, such as la commune de Paris); racism; ethnic differences (i.e. differences in language and cultural traditions); a struggle to control natural resources, mainly minerals; and the search for power for its own sake.

Two or more of these motives are usually at the origin of any given conflict and it is usually very difficult to determine with reasonable certainty which of these motives is the major driving force behind the conflict. However, examples of single course wars exist: The Biafra war was about control of the Nigerian oil fields and not much else, and the Taliban seem to have been motivated mainly by religious belief.

There are three necessary conditions for violent conflict or war to erupt:

1) A strong motivation to go to war;

2) The belief in a reasonable chance of success; and

3) Absence or weakness of mechanisms for non-violent conflict resolution.

Regarding the need for a strong motivation: everybody knows that the cost of war is quite high even for the eventual winner; it is generally catastrophic for the loser; Moreover, once a war starts the outcome is unpredictable: who would have thought that the Vietnamese would win against the Americans or the Athenians against the Persians? People have always known this, and that is the reason why most try to keep peace. It is their leaders who start wars and make great efforts to convince people to go along with something that, more often than not, is against their best interests. Virtually every warring party in all of history has been told by their leaders and their priests or shamans or mullahs that God is on their side (Bolshevism is a rare exception to this rule: the Bolsheviks believed that they had “history” on their side, which turned out not to be true). It is also useful to tell the people whom one wants to convince to put their livelihood at risk for war that they belong to a superior race and that the enemy’s country and property and women are rightfully theirs. Dehumanising the enemies by declaring them to be ethnically inferior and godless has also proven to be very effective. Since most people are gullible and greedy, they will accept some of this and similar rhetoric at face value. Most societies being strongly hierarchical, people can also be forced by their religious and secular leaders to go to war, if they don’t volunteer. In many countries, conscription has been added to this toolkit of instruments of power.

The First World War is an outstanding example of the absurdity of war. The best minds of contemporary historiography, such as Henry Kissinger (in “Diplomacy”, New York 1994), and Niall Ferguson (in “The Pity of War” London 1998) have tried hard to find a valid rationale for that war, and have failed, because there is none except the human mind’s immense potential to create havoc. And yet, the leaders of the five major European powers (the UK, France, Germany, Russia and Austria) who had been playing diplomatic and military games with each other for centuries in the so called “concert of powers” stumbled into a war that destroyed Europe’s pre-eminence in the world. They also achieved the remarkable feast of motivating their respective populations to follow them with considerable enthusiasm. They were believed when they declared that they had the right, and god, on their side and were ethnically, if not racially, superior. Each population was led to think it was bound to win. All of them lost, some more (Russia and Austria), some less (the UK).

Only rarely are military leaders caught by dangerous illusions bordering on insanity, such as Alexander (“the Great”) believing in his own invincibility and divine nature, and Hitler who probably believed in a Jewish- Bolshevik conspiration to dominate the world. Most leaders who start a war seem to genuinely believe in their military superiority and their chance to gain something from war: power, political survival, wealth, spreading their religion etc. Most of those who start a war believe that they will win if things go as planned. However, in war things rarely go as planned since a war plan is more often than not a product of wishful thinking rather than of a realistic assessment of the situation. This optimistic bias is a principal reason why it takes so little for a war to start and why only afterwards, when the war is under way, people begin to realise the amount of trouble they got themselves into.

The numerous wars since 1945 have of course the same fundamental causes as those that preceded them. In addition, they accompanied and were sometimes directly caused by the major historical developments of the time: the end of colonialism, the emergence of the cold war between the two super powers and, more recently, the power vacuum left behind in much of the South by the end of the cold war.

The main objective of European Colonialism was the peaceful commercial exploitation of the colonies. Seen from that perspective, colonialism was very successful: A tremendous transfer of wealth and income from the colonies to the respective mother country was achieved, and there was very little armed conflict in and between colonies, probably much less than in pre-colonial times and certainly much less than afterwards. The end of colonialism since 1947 was peaceful in many cases, but brought with it major wars in places where the colonialists had actually colonised, that is: settled in large numbers in the colonies. The worst was of course the Franco-Algerian war, but there were others, mainly in French Indochina, and in the African colonies of Portugal.

Decolonisation brought to an end the direct political and military domination of much of the South by a few northern countries. However, the North’s economic domination of the South continued and became even more pronounced for most commodity-exporting countries (except for oil exporting countries).

Exporting coffee, cotton, cocoa, palm oil, copper, etc, became less and less profitable. When measured against the revenue derived from exporting a certain quantity of raw materials the import of manufactured goods became more and more expensive. Expressed in economic terminology, the terms of trade of commodity-exporting countries have deteriorated more or less continuously since these countries gained their political independence.

The consequent impoverishment of large and, thanks to the progress of medical science, rapidly growing populations has contributed to political instability and the outbreak of armed conflicts. The civil war that started in 2002 in the Ivory Coast (the world’s largest cocoa exporting country), shortly after the price of cocoa dropped to a new historical low, is the most recent example of that trend.

The end of colonialism also coincided with the beginning of the so-called Cold War, which would dominate the political scene for the next forty-five years. The two superpowers avoided with some luck to go to war directly against each other, but they did not hesitate to do so through the interposition of proxies on either one or both sides, always with the intention to strengthen their own position in the cold war competition for power. On each occasion where a superpower, instead of using a proxy, fought with its own troops as in Korea, Vietnam and Afghanistan (in the 1980’s), it paid dearly for it.

More frequently, both superpowers chose to support one of the parties in an ongoing local conflict, thus ensuring in many cases prolonged bloodletting on a major scale. Angola, Nicaragua, Chad, Cambodia, Sudan, Ethiopia are typical examples.

Neither the superpowers of the cold war period nor the former colonial powers, with the exception of France, demonstrated a significant interest in preventing the countries of the South to start civil wars or wars against their neighbours, something that happened with increasing frequency. Quite often the same adversaries confronted each other repeatedly. The list of wars in Annex 1 (taken from N. Sambanis, Partition as a Solution to Ethnic War, World Politics, July 2000), while incomplete, is dreadfully long. So were the wars themselves: they lasted on average seven years.

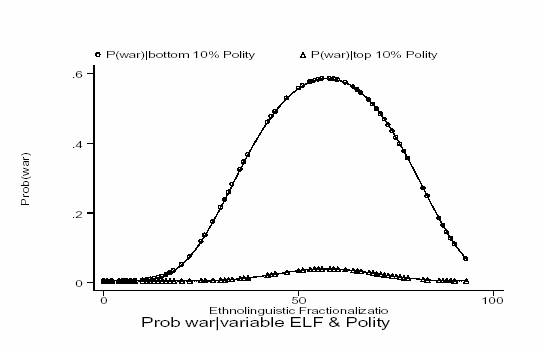

Recent research by Collier, Sambanis, Elbadawi and others at the World Bank has shed a lot of light on the causes and consequences of civil war -the dominant form of war- in the years 1960 to 1999(4). They assembled a set of data on the occurrence of civil war in 161 countries for the 40-year period 1960 to 1999. In analysing the data, one finds that the probability of civil war to occur is primarily determined by two non-economic parameters: the ethnic and religious composition of a country’s population, and the strength (or weakness) of political institutions (called “polity”) that allow citizens to participate in decision making (e.g. through elections) and provide mechanisms for non violent conflict resolution (e.g. a functioning judiciary). Strong political institutions are an excellent insurance against civil war, even if other elements, such as ethnic and religious composition and income level, are unfavourable. Even in the absence of strong political institutions, the risk of civil war is virtually zero if no ethnic or religious diversity exists in the population. The risk is also relatively low in countries with very high ethno-linguistic fractionalisation where no single ethnic group is sufficiently strong to attempt to grab power through open conflict with other groups. However, the risk of civil war is very high in the numerous countries whose ethnic composition is between those two extremes, essentially countries that are dominated by two or three ethnic groups.

If those countries also had weak political institutions, they had a 50% to 60% chance to be plagued by one or more civil wars in the forty year period 1960 to 1999. (See Figure 2a at right.)

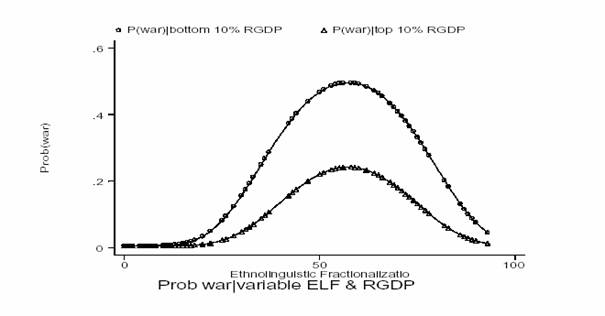

Collier et al. estimate that these two parameters – the level of ethno-linguistic fractionalisation and the strength or weakness of political institutions – explain about two thirds of the incidence of civil war. The remaining third is largely explained by economic factors, mainly the level and growth of incomes and the importance of raw material exports as a source of hard currency income: people who live comfortably have more to loose and little to gain from war, and a stagnating economy makes the poor and unemployed desperate for change. Figure 2b shows how poverty increases the risk of war by more than 20 percentage points in ethnically unstable countries.

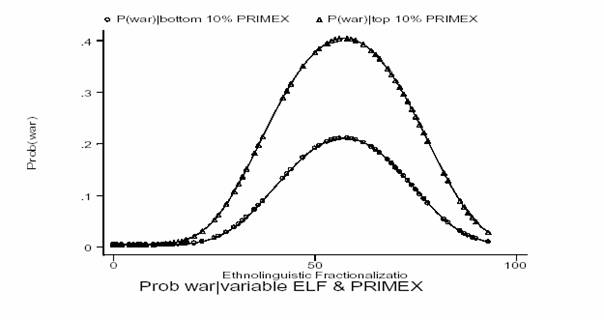

Lastly, there is the curse of wealth in natural resources: In an ethnically unstable country that is rich in one or several resources such as oil, diamonds, metals, cocoa etc. the dominant ethnic groups will try to control those resources and the income they provide; civil war will frequently be the result (see Figure 2c at right).

We can conclude that a poor, ethnically unstable country with a weak political system and a stagnating economy, but an interesting resource endowment has little chance to escape a series of civil wars as long as these conditions prevail. The two dominant variables in this equation of horrors are ethnic instability and weakness of political institutions(5).

What to do about this problem has been widely discussed. Some authors recommended partitioning of ethnically unstable countries. Partition has in fact been successful in preventing potentially violent ethnic conflicts to erupt. Recent examples are the break-up of the Soviet Union and of Czechoslovakia. However, partition has been much less successful once violent conflict has erupted, as the list in Annex 1 shows. It appears that partition as a result of war tends to let important issues unresolved, such as the rights of minorities or the control of disputed areas and natural resources, and these unresolved issues frequently lead to renewed conflict.

(3) For our purpose, the South includes in addition to the southern hemisphere, North Africa, most of Asia, the newly independent parts of the former Soviet Union except Russia and the Baltic States, and in America everything south of the Rio Grande. Conversely, the North includes Australia, New Zealand, Israel, Japan and some of the Asian Tigers.

(4) See the list of papers in Appendix 3. Bibliography

(5) In one of their papers (“Greed and Grievance in Civil War”, October 2001) Collier and Hoeffler argue that rebellion leading to civil war is mainly caused by greed combined with an opportunity for enrichment. This is not necessarily in contradiction with our conclusion, but it is a somewhat narrow interpretation of the data underlying the figures in Appendix 2. Similarly, Collier et al. argue in their latest and major publication (“Breaking the Conflict Trap; Civil War and Development Policy”, Washington D.C. 2003) that civil war is largely caused by economic issues. However, their analysis is based on a subset of only 52 wars.